Hearing on “China’s Nuclear Forces”

Testimony before the U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission

June 10, 2021

By Valerie Lincy

Executive Director, Wisconsin Project on Nuclear Arms Control

I am pleased to appear today before the U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission. The Commission has asked me to comment on China’s role in the proliferation of missile and nuclear technologies, both as a supplier and an end user, the Chinese entities that are involved in such activities, and the extent to which these activities have affected U.S. national security interests and the global nonproliferation regime.

The Wisconsin Project has long focused on the type of entity contributing to proliferation, and identifying and profiling such entities using open source data and research methods. The organization also conducts capacity building outreach on export controls, which has provided insight into the challenges China poses to the global nonproliferation regime. My testimony is therefore focused on these aspects of the proliferation threat from China.

I would characterize the present proliferation threat from China as threefold: first, entities in China continue to be a source of nuclear and missile related items to countries of proliferation concern; second, China undermines U.S.-led international efforts to use sanctions and export controls to reduce the proliferation risk from those countries, notably Iran and North Korea; and third, China is illicitly acquiring or diverting sensitive U.S. technology that increases the proliferation risk from China.

To understand the present day threat, it is useful to examine the entities involved in key imports and exports over time. This has value both because such transfers are the building blocks of, and continue to fuel, contemporary programs, and because it illustrates the changing nature of the proliferation threat from China.

Introduction

The proliferation threat posed by China has been a source of concern for the United States for several decades. However, the nature of this threat has changed during that time, in terms of Chinese exports (and other forms of support) to countries of proliferation concern, what China seeks to acquire abroad for end use in China, and the involvement of the Chinese government and state-owned enterprises (SOEs) in this trade.[1]

The 1980s and early 1990s were years that saw nuclear and missile exports from China that were consequential for proliferation to Iran, Pakistan, and Saudi Arabia, among other countries. This trade was led by newly established, state-directed firms. Illicit imports by China from the United States during this period likewise directly involved SOEs.

By the mid-1990s, China began seeking to burnish its international image with regard to nonproliferation, which led it to adopt new laws regulating trade and to support multilateral nonproliferation initiatives and regimes. This coincided with economic development in China driven by the expansion of private enterprise. From this period, China has remained a regular source of sensitive items for countries of proliferation concern, but the trade is driven by nominally private companies and individuals and involves dual-use material and technology. The Chinese government has adopted an (at best) passive response to this burgeoning trade, neither actively preventing nor punishing private entities for such exports or re-exports.

Similarly, the Chinese government has balked at preventing its territory from hosting proliferation facilitators who provide financial and other support for North Korea, in violation of U.N. sanctions. Such facilitation has provided the Kim regime with billions of dollars in funds that could be used to support North Korea’s nuclear and missile programs.

SOEs remain leading exporters of technology for nuclear energy programs and of unmanned aerial vehicles, which undermine the global nonproliferation regime. However these companies no longer transfer fissile material or fissile material production equipment to countries without the requirement of International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) safeguards, as was the case in earlier decades. SOEs also are responsible for misusing imports of advanced U.S. nuclear technology in the context of cooperative agreements with U.S. firms. This has led the U.S. Department of Energy to conclude that such imports pose a risk of proliferation or military diversion in China.[2] More recent trends reflect an effort by SOEs to use evasive techniques and exploit state-led hacking to obtain U.S.-controlled technology.

More broadly, the role of SOEs in carrying out formal Chinese government policies, such as Military-Civil Fusion (MCF), Made in China 2025, and the Strategic Emerging Industries Plan, should also be seen as a proliferation threat. Such policies seek to exploit the tools of modern commerce and the overlap between the commercial and military demand for dual-use technologies as a means of enhancing China’s defense industrial base. Recent action by the U.S. government has rightly taken aim at this practice by targeting SOEs with financial, trade, and other restrictions.

Finally, China’s expanding economic influence in many parts of the world makes it more difficult for the United States to convince partner countries to support U.S. counter and nonproliferation policies and undermines U.S. export control and nonproliferation capacity building in these countries.

Past nuclear and missile transfers by SOEs fueled proliferation that continues to present a challenge today.

The Chinese government and prominent Chinese SOEs were at the forefront of strategically significant transfers in the 1980s and early 1990s. These transfers have served as the building blocks for nuclear weapon and weapon delivery programs in countries not party to the nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) that have developed nuclear weapons, in countries that have violated their NPT commitments, as well as in countries that have expressed a willingness to abrogate NPT commitments.

Major, confirmed nuclear-capable missile transfers ended following a series of commitments by the Chinese government beginning in the mid-1990s not to help states develop ballistic missiles capable of delivering nuclear weapons, using the Missile Technology Control Regime (MTCR) parameters to define such systems. Similarly, Chinese SOEs have increasingly observed nuclear nonproliferation norms in their nuclear export policies and practices. More recent transfers, while bounded to some extent by these norms, nevertheless have negative consequences for the nonproliferation regime.

I will examine several countries that have greatly benefited from Chinese support, describing key transfers over time and the Chinese entities involved in those transfers.

Pakistan

The Chinese government has strong historic links to Pakistan’s nuclear weapon and missile programs. China provided Pakistan with the material and expertise that served as the foundation for its nuclear weapon program from its inception, from sharing the complete design of a tested nuclear weapon in the early 1980s, to the supply of weapon-grade uranium to fuel the design, to support in helping Pakistan produce its own weapon-grade uranium using gas centrifuges.[3]

China also provided Pakistan with a means of nuclear weapon delivery, with the export of the solid-fueled, short-range DF-11 (M-11) ballistic missile in the early 1990s.[4] This sale equipped Pakistan with a reliable, nuclear capable delivery system as it was in the midst of developing a nuclear weapon, which it would first test in 1998. This transfer was made by a now-notorious SOE, China Precision Machinery Import-Export Corporation (CPMIEC), which markets and sells missiles abroad on behalf of other state-owned firms.[5]

Between 1994 and 1995, another state-owned enterprise, China Nuclear Energy Industry Corporation (CNEIC), shipped 5,000 ring magnets to Dr. A.Q. Khan Research Laboratories, a facility in Pakistan not subject to international nuclear safeguards.[6] Ring magnets are key components that stabilize centrifuges used in uranium enrichment. Again, the timing of the transfer was critical; Pakistan was actively developing nuclear weapons. The transfer from a subsidiary of China National Nuclear Corporation (CNNC), which is China’s largest nuclear energy SOE,[7] to one of the primary research organizations working on Pakistan’s nuclear weapon program left no doubt that the export was a knowing contribution to Islamabad’s accelerating nuclear effort.

While China may have since ceased direct transfers in support of Pakistan’s nuclear weapons program, the nuclear partnership between the two countries remains extensive and problematic. China is Pakistan’s primary nuclear partner, supplying a string of power reactors despite a commitment to avoid such sales to countries that do not have a comprehensive safeguards agreement with the IAEA, which Pakistan does not.[8] When China joined the Nuclear Suppliers Group (NSG) in 2004, it indicated that it would continue to provide fuel and other services for the two reactors it had built at the Chashma facility (CHASNUPP-1 and CHASNUPP-2). Then in 2010, China announced that it would build two more reactors at Chashma (CHASNUPP-3 and CHASNUPP-4), arguing that these new units were grandfathered by a previous bilateral agreement with Islamabad.[9] In 2013, China and Pakistan signed an agreement for the construction of two additional reactors in Karachi (KANUPP-2 and KANUPP-3). Most recently, in 2017, China signed an agreement with Pakistan to build a fifth reactor at Chashma.[10]

SOEs play a vital role in these projects. All four operational reactors at Chashma were constructed by CNNC subsidiary China Zhongyuan Engineering Corporation (CZEC).[11] CZEC also built KANUPP-2, is currently building KANUPP-3,[12] and will build the fifth reactor at Chashma.[13] Another CNNC subsidiary, CNEIC, supplied fuel assemblies and related core components to KANUPP-2 and KANUPP-3 in 2020, according to trade data reviewed by the Wisconsin Project. CNNC’s main Pakistani counterpart in these projects is the Pakistan Atomic Energy Commission (PAEC). Since 1998, PAEC has been on the U.S. Department of Commerce’s Entity List of end users subject to heightened export license requirements due to involvement in proliferation activities,[14] in response to Pakistan’s nuclear weapon tests that year.

While the reactor projects described above are subject to site-specific IAEA safeguards, China’s nuclear assistance to Pakistan nevertheless presents several proliferation challenges. First, it undermines China’s NSG commitment. Second, it allows Pakistan to devote more of its unsafeguarded nuclear infrastructure to fissile material production for nuclear weapons. Islamabad produces enough fissile material for approximately 14 to 27 nuclear warheads per year, according to estimates from non-governmental experts.[15] Third, it provides Pakistan access to advanced nuclear technologies that would not otherwise be available to it, which could ultimately benefit the unsafeguarded program.

Major missile-related transfers from SOEs to Pakistan declined after China agreed to adhere to (some) MTCR export standards. But such transfers have not ceased. In 2014, for example, Wuhan Sanjiang Import and Export Co. Ltd. shipped defense-related items to Pakistan’s National Development Complex (NDC), which develops the Shaheen series of solid-fueled ballistic missiles.[16] Wuhan Sanjiang is subordinate to China Aerospace Science and Industry Corporation (CASIC).[17] In 2017, Wuhan Sanjiang shipped components with applications in missile transporters and launchers to an entity connected to Pakistan’s nuclear and missile work.[18]

Pakistan is also a beneficiary of China’s expansive armed drone exports, including MTCR category I or near-category 1 systems, as well as the ability to produce them. These systems are produced by SOEs such as China Aerospace Science and Technology Corporation (CASC) and highlight the problematic nature of China’s voluntary adherence to the MTCR.[19]

Saudi Arabia

As Iran expands its nuclear program, there is ongoing concern that Saudi Arabia may seek to hedge against a future Iranian nuclear weapon by building its own expansive nuclear energy program. For instance, Saudi Arabia plans to build nuclear power reactors and has so far been unwilling to accept restrictions on uranium enrichment and reprocessing in the context of a nuclear technology cooperation agreement with the United States. Early transfers from SOEs in China provided Saudi Arabia with a means of nuclear weapon delivery and more recent support could improve delivery capability and help the Kingdom develop an indigenous uranium enrichment program.

In a well-document case from 1988, China supplied 36 DF-3 (CSS-2) liquid-fueled, intermediate-range ballistic missiles to Saudi Arabia.[20] The sale was negotiated by Poly Technologies, a firm formed in 1984 through the joint investment of China International Trust and Investment Corporation (CITIC) and the General Armament Department of the People’s Liberation Army (PLA).[21] This was the first time that any country had sold intermediate-range missiles to a country in the Middle East and the first time that China had sold a strategic missile. The DF-3 was used in the Chinese arsenal to deliver nuclear warheads over 1,500 miles. Because of its poor accuracy, the DF-3 was considered suitable mainly for nuclear missions, making it a worrisome choice for Saudi Arabia, a country without nuclear weapons; however, the variant sold to Saudi Arabia was reportedly modified to allow it to carry a conventional payload. The sale included assistance in the construction of two missile bases south of Riyadh, as well as the provision of Chinese military personnel for help with maintenance, operations, and training.[22]

In 2007, Saudi Arabia reportedly received China’s DF-21 (CSS-5) ballistic missile,[23] a solid-fueled, medium-range missile, with both nuclear and conventional variants. The missile is a product of China’s largest missile producer, CASIC.[24] The alleged transfer would provide Saudi Arabia with a shorter-range but more mobile and accurate alternative to the DF-3 – more effective for conventional missions but also potentially providing the Kingdom with a much-improved nuclear weapon delivery option. Little is known about those involved in negotiating the alleged transfer of the DF-21 and China has not confirmed it. However, any such transfer could not take place without the involvement of the state. The transfer allegedly took place well after the Chinese government’s pledge to follow MTCR export standards.

Most recently, in 2019, open source analysis by private research groups indicate that Saudi Arabia has built a solid fuel missile engine production and test facility at al-Watah, possibly with Chinese assistance.[25] The location had previously been identified as a missile base but commercial satellite imagery indicates new construction elements that would support missile production.[26] Again, this support would have been provided after China’s informal MTCR adherence and necessarily would have involved the state.

Saudi Arabia has also benefited from armed drone exports from China, potentially including MTRC category I or near-category 1 systems, as well as production lines. Armed drones produced by SOEs Aviation Industry Corporation of China’s (AVIC) Chengdu Aircraft Industry Group (CAIG) and CASC have been delivered to the Kingdom, and a license agreement allowing for domestic production of such systems has reportedly been signed.[27] These sales undermine U.S. efforts to control the proliferation of armed drones, with China serving as a ready supplier of such technology with little to no requirements placed on potential clients.

Leading Chinese SOEs are also involved in Saudi Arabia’s civilian nuclear energy and nuclear material mining programs. In 2016, China Nuclear Engineering and Construction Corporation (CNECC), a CNNC subsidiary, signed a memorandum of understanding with King Abdullah City for Atomic and Renewable Energy to construct a high-temperature gas-cooled reactor in Saudi Arabia.[28] In 2017, CNNC signed a memorandum of understanding with the Saudi Geological Survey (SGS) to explore uranium and thorium deposits in Saudi Arabia.[29] That same year CNECC reportedly signed a memorandum of understanding with the Saudi Technology Development Corporation to study the feasibility of constructing a high-temperature reactor seawater desalination plant in Saudi Arabia.[30] In 2019, another CNNC subsidiary, the Beijing Research Institute of Uranium Geology (BRIUG), reportedly completed a survey of Saudi uranium ore reserves, identifying reserves that could produce over 90,000 tons of uranium.[31] In the same year, BRIUG held talks with the Saudi Ministry of Industry and Mining on uranium and thorium exploration projects in Saudi Arabia.[32] While these activities all relate to civilian nuclear energy development plans, they nonetheless undermine U.S. efforts to convince the Kingdom not to pursue uranium enrichment, which would increase Saudi Arabia’s latent ability to develop nuclear weapons in the future.

Iran

China was an early supporter of Iran’s nuclear program in the years after the Iran-Iraq War, when that program was once again moving forward. China is believed to have supported uranium mining in Iran, including at the Saghand uranium mine.[33] Experts from BRIUG have conducted scientific exchanges with Iranian nuclear scientists and Chinese experts allegedly participated in exploration work in Iran.[34] China is also widely acknowledged to be the source of information for the conversion plant at Isfahan. Despite a 1997 agreement with the United States to end cooperation with Iran in the nuclear field, China appears to have provided Iran with a blueprint for the plant as well as design information and test reports for equipment.[35]

Both the Saghand mine and conversion plant remain in operation today. They are key facilities in the front end of Iran’s nuclear fuel cycle, providing a domestic source of uranium hexafluoride – the feedstock for Iran’s gas centrifuge enrichment program.[36]

Beijing has also been a major supplier of ballistic missile technology to Iran, beginning in the late 1980s. In 1998, the Commission to Assess the Ballistic Missile Threat to the United States reported that China had “carried out extensive transfers to Iran’s solid-fueled ballistic missile program.”[37] In June 2006, the U.S. Treasury Department sanctioned CPMIEC for the sale of MTCR-controlled goods to Shahid Bagheri Industrial Group (SBIG), an organization responsible for Iran’s solid-fueled ballistic missile program.[38]

SOEs continue to play a role in supplying Iran’s missile program, although they have done so less overtly than in previous decades. In 2017, the Treasury Department sanctioned Wuhan Sanjiang Export and Import Co. Ltd. for selling more than $1 million worth of navigation-related gyrocompasses and specialized sensors to Shiraz Electronics Industries (SEI), a producer of military electronics subordinate to Iran’s Ministry of Defense and Armed Forces Logistics (MODAFL).[39] The State Department also sanctioned Wuhan Sanjiang in February 2020 pursuant to the Iran, North Korea, and Syria Nonproliferation Act (INKSNA) for supporting Iran’s missile program.[40]

North Korea

SOEs have provided some support for North Korea’s ballistic missile program through technology and knowledge transfers since the 1990s. In 1998, SOE China Academy of Launch Vehicle Technology (CALT), a CASC subordinate,[41] allegedly worked with North Korea on its space program to develop satellites, with reports suggesting that the cooperation may have been linked to development of the Taepodong-1 medium-range ballistic missile. In 1999, China reportedly sold specialty steel with missile applications to North Korea, as well as accelerometers, gyroscopes, and precision grinding machinery.[42]

While Chinese support for North Korea’s missile program shifted away from SOEs after the 1990s, one notable exception was the 2011 transfer of six eight-axle, off-road lumber transporters manufactured by Hubei Sanjiang Space Wanshan Special Vehicle Co., Ltd and exported by Wuhan Sanjiang Import and Export Co. Ltd. Both firms are subordinate to China Space Sanjiang Group Co., Ltd., which is overseen by CASIC.[43] Subsequent investigations by the United Nations and the United States concluded that North Korea had illicitly converted the vehicles to ballistic missile transporter-erector-launchers (TELs), and the United Nations recommended that countries deny the export of such items to North Korea. China is known to have disregarded this recommendation on at least one occasion, exporting three-axle trucks that were converted by North Korea for use transporting guided artillery rockets.[44] The trucks were reportedly manufactured by China National Heavy Duty Truck Group Co., Ltd. (Sinotruk), an SOE truck manufacturer.[45]

Chinese SOEs have had little involvement in nuclear-related proliferation to North Korea. However, China’s support to Pakistan’s nuclear program is recognized as a case of secondary proliferation to North Korea. North Korea is believed to have received technology and knowledge transfers from Pakistan and the A.Q. Khan network, which was originally supplied by SOEs.[46]

The rise of the private actor: Recent transfers and support by China-based entities make it more difficult to address challenges to the nonproliferation regime.

Since the early 1990s, China has increasingly observed international non-proliferation norms and multilateral export control regimes, for instance by ratifying the NPT in 1992, joining the Zangger Committee in 1997, and joining the NSG in 2004. Alongside these actions, China has formalized and expanded its national export control laws to reflect these norms and regimes. While Beijing’s formal application to join the MTCR in 2004 was rejected, the government nevertheless committed to adjust its missile technology control lists to match those of the MTCR (though not comprehensively).[47] China has also held discussions with the Wassenaar Arrangement and has pledged to align itself with the group’s controls on conventional arms and dual-use goods and technologies.

While the export practices of SOEs appear to have improved in conjunction with these national nonproliferation commitments, the problem of proliferation from China remains – perhaps most acutely in the form of Chinese-based companies and individuals transferring dual-use items. This trade involves both controlled goods as well as items below control thresholds that still have applications in nuclear and missile programs. While the activity may not be government directed, it is tolerated if not openly encouraged by the state.

In addition, China hosts entities that facilitate proliferation, particularly to North Korea, through the evasion of sanctions and illicit financing. Here too, the government has taken little action against these facilitators, despite numerous detailed reports from the United Nations about the nature and scope of their support.

The contribution of these private actors in proliferation-related trade and support from China, beginning in the 2000s, has expanded over the past decade. Examples of how they have helped North Korea, Iran, Pakistan, and Syria are described below.

North Korea

While private actors in China support North Korea’s acquisition of dual-use goods, the primary contribution of these actors to North Korea’s missile and nuclear programs in recent years has been indirect: facilitating Pyongyang’s access to foreign currency used to fund these programs. The China-based actors providing this support are trading companies and individuals with no direct connection to the state. This support falls into three main categories: hosting entities that are part of North Korean financial networks; hosting North Korean nationals who remit their income; and allowing private entities to facilitate the evasion of sectoral sanctions.

1. North Korean Financial Networks in China

China-based entities provide financial services for North Korea in violation of U.N. sanctions.[48] For instance, a network of representatives and front companies linked to North Korea’s Foreign Trade Bank (FTB), which was sanctioned by the United Nations in August 2017,[49] operate in China. In February 2020, the United States indicted individuals linked to FTB, including six North Korean nationals based in China and four Chinese nationals, for their roles in facilitating over $2.5 billion in illegal transactions through over 250 front companies, including front companies based in China.[50]

China-based trading companies also facilitate North Korea’s access to the financial system by importing prohibited goods, such as coal, and transferring payment for the goods to North Korean front companies in China that use the proceeds to purchase commodities on behalf of North Korea. For example, Dandong Zhicheng Metallic Material Co., Ltd., a Chinese trading company, operated a network of front companies to facilitate transactions and bulk commodity purchases on behalf of North Korea via the sale of North Korean coal.[51]

North Korea also takes advantage of “over the counter” brokering services based in China with weak “know your customer” protocols to launder stolen cryptocurrency and convert it into fiat currency, including with the help of Chinese nationals.[52]

2. North Korea Individuals Based in China

North Korean workers continue to reside in China and earn income that is remitted to North Korea, in violation of a U.N. Security Council resolution that requires countries to repatriate all North Korean nationals generating revenue abroad no later than December 2019.[53]

For example, North Korean information technology (IT) workers linked to the U.N.-sanctioned Munitions Industry Department (MID), which oversees North Korea’s nuclear and missile programs, have established Chinese companies and sponsored visas for North Korean workers, according to the U.N. Panel of Experts on North Korea. In 2019 and 2020, the Panel documented over 500 IT and other North Korean workers based in China.[54] Chinese companies that have worked with North Korea IT workers are allegedly aware of their links to North Korea.[55]

Representatives of U.N.-sanctioned entities involved in procurement for North Korea’s military, nuclear, and missile programs, such as Korea Ryonbong General Corporation and Namchongang Trading Corporation, have also operated out of China.[56]

3. Lax Enforcement of U.N. Sectoral Sanctions

Chinese entities also help North Korea breach an annual cap set by the United Nations[57] on refined petroleum imports and a U.N. prohibition on coal exports.[58] China is one of only two countries (with Russia) to report refined petroleum shipments to North Korea, but claims there is insufficient evidence to reach the conclusion that North Korea is breaching the U.N. cap.[59] Yet China-flagged vessels have been involved in direct deliveries of refined petroleum products to North Korea, in addition to conducting ship-to-ship (STS) transfers for refined petroleum shortly before making port calls in North Korea.[60] China also allows vessels suspected of involvement in illicit petroleum exports to North Korea to enter its territorial waters without penalty.[61]

China continues to import North Korean coal and allow ship-to-ship (STS) transfers of coal in its waters, primarily in the Ningbo-Zhoushan area. According to the U.N. Panel of Experts, from January through September 2020, North Korea exported over 2.5 million tons of coal to China’s territorial waters. To avoid detection, North Korean vessels engaged in STS transfers of coal with China-flagged vessels, which subsequently delivered the coal to Chinese ports, according to the U.N. Panel.[62]

4. Dual-use Transfers

Private entities in China are also supplying North Korea with dual-use items; these same entities may also be suppliers to Chinese SOEs. For instance, in 2013 and 2016, Shanghai Zhen Tai Instrument Corporation Limited supplied pressure transducers to North Korean national Kang Mun Kil, a China-based representative of U.N.-sanctioned Namchongang Trading Corporation, for export to North Korea.[63] Shanghai Zhen Tai Instrument Corporation Limited also supplies SOE CNNC.[64]

In another example, investigations of missile debris conducted by the U.N. Panel of Experts have revealed China to be the source of missile and space launch vehicle components, including pressure transmitters and camera electromagnetic interference filters. These components were either manufactured or sold by private Chinese companies, according to the Panel. In one instance, North Korea procured the components from a Chinese firm that apparently sold them via an electronics market.[65] Many of these items fall below control thresholds, emphasizing the need for China to implement strong “catch-all” controls.[66]

Iran

Publicly documented transfers of concern from China to Iran over the past decade or more are predominantly carried out by small, private enterprises and individuals, with no clear government involvement. These transfers can be divided into two broad categories: those in which Chinese entities are active conspirators, and those in which China hosts Iranian sanctions evaders.

1. Chinese Entities as Active Conspirators

Chinese nationals, often using their own China-based companies, have been active participants in schemes to transfer dual-use items to Iran. Karl Lee (also known as Li Fang Wei) personifies this category. Lee, a businessman operating out of Dalian, China, became notorious for being behind a string of sales, beginning in the late 2000s, made directly to ballistic missile developers in Iran. Using a cluster of China-based front companies, Lee shipped gyroscopes, accelerometers, high-strength alloys, graphite cylinders, and other items to SBIG. Lee has been sanctioned repeatedly by the State Department – twelve times since 2010, most recently in May 2019.[67] He was indicted twice in New York, most recently in 2014,[68] for making transfers through U.S. banks in connection with his illicit transactions, effectively using the U.S. financial system to facilitate his proliferation efforts.

Despite the sanctions and indictments, the Chinese government does not appear to have applied any pressure to Lee to cease his trade with Iran. A 2018 study suggests that Lee remains active in Dalian, China, assisted by family members in the operation of his network of front companies.[69] In 2019, the U.S. State Department concluded that Lee’s support has helped Iran improve the accuracy, range, and lethality of its missiles.[70]

Chinese businessman Sihai Cheng provides another example. From 2005 through 2012, working in cooperation with an Iranian national, Cheng supplied thousands of items to an Iranian firm involved in the country’s uranium enrichment program.[71] Some of these items were of Chinese origin and included titanium sheets and tubes, seamless steel tubes, pressure valves, bellows, and flanges. Cheng also managed to procure hundreds of U.S.-origin pressure transducers, a component that is essential for the operation of centrifuges used in uranium enrichment. Cooperating with employees at a China-based subsidiary of a leading U.S. manufacturer of pressure transducers, Cheng was able to use front companies in China to act as false end users for the exports. He then re-routed the shipments to Iran upon their arrival in China. This scheme only came to an end when Cheng was arrested in London in 2014 and extradited to the United States for trial, where he was sentenced to nine years in prison.[72] China took no action against Cheng or his co-conspirators, and Chinese government officials reportedly objected to the United States taking export enforcement actions against Chinese nationals.[73]

A third example involved Zongcheng Yi, a Chinese national who conspired with Iranian national Parviz Khaki between 2008 and 2011 to obtain U.S.-origin dual-use items including maraging steel, aluminum rods, pressure transducers, vacuum pumps, lathes, and nickel alloy on behalf of Iranian end users. Yi allegedly used his Guangzhou-based company to arrange purchases of these items from unwitting U.S. suppliers and their transshipment to Iran via Hong Kong.[74] Yi remains at large, presumably in China; U.S. prosecutors moved to dismiss the case against him in August 2020, apparently so as not to continue expending resources prosecuting a fugitive whose arrest is unlikely.[75]

2. Iranian Sanctions Evaders Active in China

In other instances, Iranian individuals and companies have operated freely from inside China to arrange transfers of dual-use items, either without the direct involvement of Chinese nationals or with Chinese nationals playing only supporting roles as local facilitators.

The activities of Rayan Roshd Afzar Company, a Tehran-based defense production firm that has supplied components to the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC)’s UAV and aerospace programs,[76] are illustrative of this pattern. Rayan Roshd Afzar’s parent company, Rayan Group, operated out of Beijing as recently as 2017,[77] and the Treasury Department’s press release sanctioning Rayan Roshd Afzar that year alleged that company officials had “obtained a range of military-applicable items from China.”[78]

In another scheme running from 2011 to 2017, Iranian-born Canadian national Ghobad Ghasempour set up several front companies in China with the aid of a Chinese national, Yi Xiong, for the purpose of transshipping a variety of dual-use items from the United States, Germany, and Canada through China to Iran. These items, some of which shipped successfully, included a precision lathe machine, thermal imaging cameras, and an inertial guidance system test table (which can be used to test missile guidance systems), all of which are subject to U.S. export controls. Their ultimate recipient was alleged by U.S. prosecutors to be an Iranian state-controlled engineering company that purchases items for Iranian government agencies. Ghasempour was arrested in the United States in 2017 and sentenced to 42 months in prison,[79] but Xiong remains at-large, presumably in China.

There are numerous other instances of Iranian sanctions evaders using China-based front companies to transship nuclear and missile dual-use materials from third countries to Iran, during a period when Iran’s uranium enrichment program was expanding. The contents of these shipments have included: carbon fiber (one Japanese-origin shipment seized in 2012 en route from China to Bandar Abbas);[80] aluminum powder (one North Korean-origin shipment seized in 2010 en route from China to Bandar Abbas);[81] and U.S.-origin dual-use electronics (with multiple attempts documented between 2007 and at least 2011).[82]

China does not appear to have taken concerted action to prevent its territory from being used as a base of operations and transshipment point for Iranian sanctions evaders, nor to prevent its nationals from facilitating or participating in schemes to transfer dual-use items to Iran.

Syria

Syria has relied on China-based front companies to facilitate delivery of chemical weapon- and ballistic missile-related items from North Korea, which is Syria’s primary source of supply. In the period from 2007 to 2012, for instance, these Chinese companies transferred equipment for Scud missile propellant,[83] alloy tubes for manufacturing rockets,[84] graphite cylinders with ballistic missile applications,[85] and items used in the handling of military-grade chemical agents.[86] In many cases, the Syrian end users were front companies or subsidiaries of the Scientific Studies and Research Center (SSRC), which oversees Syria’s chemical weapon and ballistic missile programs.

China also hosts several SSRC affiliates. Since 2018, the French government has designated four of these affiliates for their involvement in the procurement of chemical weapon- and ballistic missiles-related items, including precursors for sarin gas.[87] North Korea also appears to source dual-use items from Chinese firms for supply to Syria.

Pakistan

The rise in support from private Chinese firms to Pakistan began over a decade ago. In a report to Congress on proliferation in 2011, the Director of National Intelligence assessed that “Chinese entities – primarily private companies and individuals – continue to supply a variety of missile-related items” to Pakistan.[88]

More recently, the U.S. Commerce Department has designated numerous Chinese companies for supplying Pakistan’s missile and unsafeguarded nuclear programs with dual-use goods. One such company, Taihe Electric (Hong Kong) Limited (which has offices in Chengdu and Hong Kong), was designated in August 2020.[89] Taihe Electric supplies Pakistani front companies, as well as PAEC subsidiaries and the Chashma plant.[90] In some cases the items originate in China, while in others they are transshipped through China from other countries, including the United States. Typically the declared Pakistani end user is a front company and the transfers are in fact destined for government entities subject to U.S. trade restrictions, including PAEC and the Advanced Engineering Research Organization (AERO).[91]

The proliferation threat from SOEs: End users of U.S. controlled technology.

In addition to the outward proliferation from China described above, SOEs have long sought U.S.-origin controlled goods and technology illicitly. SOEs have pursued three acquisition paths for such transfers: by exploiting direct collaboration with U.S. firms, through brokers, front companies, or other evasive tactics to mask the ultimate end user, and through acts of theft or espionage. SOEs that direct nuclear and missile work in China, as well as related exports, have been among the beneficiaries.

Direct Collaboration, Joint Ventures, and Technology Transfer

During the 1990s, as China began reforming its defense industry, the Chinese government increasingly encouraged Chinese companies operating in strategic sectors to focus on civilian, dual-use markets related to those sectors. At this time, China’s domestic technology lagged behind that of the United States and other developed nations. Chinese companies sought to form joint ventures (JVs) with leading U.S. firms, as a means of gaining access to key equipment and technical know-how.[92] During the 1990s, accordingly, cases of Chinese acquisition of U.S. dual-use technology often arose from collaboration between prominent American firms and their Chinese counterparts.

For instance, as part of a joint project between China National Aero-Technology Import-Export Corporation (CATIC) and McDonnell Douglas for the production of airliners in China, U.S.-origin machine tools were transferred to factories in China overseen by AVIC, for use only in the production of civilian aircraft.[93] The machine tools were transferred to companies under AVIC involved in military projects, including anti-ship cruise missile production.[94]

Chinese companies may use such cooperation as a stepping stone, gaining manufacturing know-how and then cutting out their foreign partner. The case of Westinghouse and CNNC provides an illustrative example of this dynamic. In the 2000s and early 2010s, Westinghouse worked with CNNC to jointly produce pressurized water reactors for use in China with designs from Westinghouse.[95] According to a U.S. Department of Justice indictment related to a hack of Westinghouse’s systems, information stolen from Westinghouse around May 2010 included design and technical specifications related the AP1000 pressurized water reactor that would “enable a competitor to build a plant similar to the AP1000 without incurring significant research and development costs.”[96] Although the indictment does not identify the beneficiary of the hacked information, it was reportedly CNNC.[97] CNNC now produces the Hualong One pressurized water reactors, cutting Westinghouse out of China’s nuclear power plant construction market.[98]

Circumventing Trade Controls Via Subsidiaries and Front Companies

SOEs have relied on evasive procurement tactics since the mid-2000s, as a means of skirting increasingly strict U.S. export controls in order to obtain dual-use technology. These tactics included using obscure U.S.-based brokers to obtain such technology from unwitting U.S. manufacturers, the use of foreign procurement agents, and transshipment through third countries.

Beginning in the 2000s, SOEs began using small U.S.-based companies as a source of illicit supply. These firms often do little or no business outside of exports to China, and sometimes deal with a sole customer. For instance, a family-run firm based in New Jersey procured and supplied integrated circuits and components to two institutes under China Electronics Technology Group Corporation (CETC),[99] the 14th and the 20th Institute, both of which are involved in the development of military electronics and have conducted research on ballistic missiles.[100]

The case of Hong Wei Xian also illustrates this trend. Hong, a Chinese national, was arrested in 2010 for attempting to procure, on behalf of CASC, more than 1,000 radiation-hardened programmable read-only memory (PROM) microchips designed to withstand space-based conditions.[101] He operated his own company, Beijing Starcreates Space Science and Technology Development Company Limited, which based much of its business on importing these microchips to supply CASC. In order to evade detection, Hong requested that a Virginia-based supplier send the components in smaller quantities to several third countries, where they would be transshipped for ultimate delivery to China.[102]

Chinese companies also sought expertise from the United States. China General Nuclear Power Company (CGNPC), a leading nuclear SOE,[103] was charged in 2016 with conspiring to produce special nuclear material outside the United States with U.S. technical consulting. Between 1997 and 2016, a CGNPC employee created a Delaware-based company, Energy Technology International, to facilitate technical consulting from U.S. experts on CGNPC’s Small Modular Reactor Program, Advanced Fuel Assembly Program, Fixed In-Core Detector System, and other nuclear reactor-related computer programs. According to the U.S. Department of Justice, this CGNPC employee organized flights and payments for U.S.-based experts to travel to China and provide consulting services.[104]

Major Chinese research universities affiliated with military research programs have also used these methods to procure U.S. technology. In one recent case, Northwest Polytechnical University (NWPU) used a middle man, Shuren Qin, and his U.S.-based company, LinkOcean Technologies, LTD., to illicitly import technology with underwater and marine applications to China from the United States, Canada, and Europe without export licenses. These items included at least 50 hydrophones for use in anti-submarine warfare, side scan sonar systems, unmanned underwater vehicles, and robotic boats. NWPU has been listed on the Commerce Department’s Entity List since 2001, so the university would not have otherwise received permission for these imports.[105]

Theft and Espionage

Chinese SOEs have relied on trade secret theft and espionage, occasionally carried out by employees of the SOEs but more often by organs of the Chinese central government, including the Ministry of State Security (MSS) and People’s Liberation Army (PLA). The beneficiaries of trade secrets obtained through these actions are likely SOEs, although such a connection is not always easy to establish.

In one such example, a Chinese MSS operative, Yanjun Xu, attempted to steal aerospace technology from U.S. companies, including General Electric.[106] Xu worked with China’s leading aerospace engineering-focused university, the Nanjing University of Aeronautics and Astronautics (NUAA), to fly employees of leading U.S. aerospace firms to China to recruit them as spies for China’s aerospace research programs. Xu and his associates at NUAA successfully obtained sensitive company information from at least one engineer at an undisclosed leading U.S. aerospace company.[107]

These espionage activities also occur over the internet, facilitated by China’s advanced cyberattack capabilities. In one case, beginning around 2006, Chinese nationals Zhu Hua and Zhang Shilong, two members of a Chinese MSS hacking unit, targeted the computer systems of leading U.S. firms in dual-use sectors. These hacks provided the MSS with data from seven companies in the aviation/aerospace industry, three companies involved with communication technology, three companies in the advanced electronics systems, a company in the maritime industry, NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center and Jet Propulsion Laboratory, and the Department of Energy’s Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, among others.[108]

Conclusion and policy recommendations

The nonproliferation regime is constructed around the NPT, buttressed by technology controls set forth in multilateral supply regimes that are implemented through national regulations, and enforced through U.N. and other sanctions and counterproliferation measures. Despite a series of nonproliferation pledges and commitments over decades, the actions of the Chinese state, SOEs, and China-based entities have continued to undermine each component of this regime, as illustrated in the examples above. Through its actions, China continues to:

- selectively ignore MTCR and NSG-related commitments when commercial or other imperatives have prevailed;

- support the evasion of U.N. sanctions on Iran and North Korea by hosting firms and individuals supplying or financing those countries; and

- flout U.S. export controls and cooperative agreements in order to obtain sensitive technology.

In light of these trends, U.S. policy vis-a-vis China has shifted from seeking engagement with China to a more competitive paradigm. It remains useful and important for the United States to press China to fulfill its NSG commitments, to join and fully adhere to the MTCR, and to enforce U.N. sanctions and its new comprehensive export control law. However, the U.S. policy shift would also benefit from pursuing, in tandem, the following more punitive measures:

- Continue to Target China-based Suppliers of Proliferation Concern and Sanctions Evaders

- Take Public Action on U.N. Findings on North Korea to Circumvent Chinese Obstruction

- Expand the Chinese Military-Industrial Complex List (NS-CMIC List)

- Mitigate the Proliferation Risk Posed by Cooperation with Chinese Universities

- Support the Development of a CFIUS-like Review Process in Partner Countries

Continue to Target China-based Suppliers of Proliferation Concern and Sanctions Evaders

Most private firms and individuals operating in China and supplying countries of concern, as well as Chinese SOEs, may not have a footprint in the United States and therefore may not be harmed economically by the imposition of U.S. sanctions. Designating them and publicizing their support nevertheless has value for U.S. nonproliferation objectives. First, it raises awareness among U.S. suppliers about the ongoing risk of illicit procurement when dealing with potential new clients and the critical role that China-based entities play in this trade. Second, it identifies specific parties involved; while these parties may not have assets or interests in the United States, they may well operate in other countries. Their operations there could be harmed once U.S. sanctions, particularly secondary sanctions, are enacted. Third, it provides U.S. partners with information they can use to prevent proliferation.

Take Public Action on U.N. Findings on North Korea to Circumvent Chinese Obstruction

The U.N. Panel of Experts has recommended numerous entities and vessels for designation by the Security Council’s 1718 Committee. However, none have ultimately been sanctioned, largely because of the unwillingness of China (and Russia) to support such action. This harms the overall implementation of U.N. sanctions against North Korea and deprives a number of countries that are regularly exploited by North Korean sanctions evaders of clear guidance on how to counter their actions.

The United States could raise awareness about the Panel’s findings through the imposition of sanctions on these entities and vessels. Of the 25 entities and individuals and 31 vessels recommended for designation since the Panel’s March 2018 report, only one entity, two individuals, and two vessels have been sanctioned by the United States, and these sanctions were already in effect when the Panel made its recommendations. U.S. sanctions play a key role in public diplomacy efforts to increase compliance with U.N. sanctions and send a strong signal to countries implementing these sanctions.

The United States should also continue to publish advisories highlighting information presented in the Panel reports, in particular typologies of North Korean sanctions evasion tactics. This information provides partner countries with tangible steps they can take to counter North Korean procurement and more effectively enforce sectoral sanctions. U.S. government advisories are widely disseminated among public and private sector actors and have been useful in the past in engaging countries on improving their implementation of U.N. sanctions.[109]

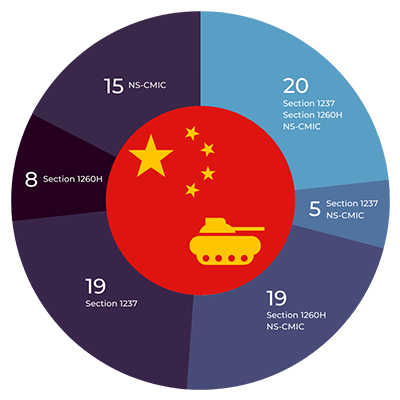

Expand the Chinese Military-Industrial Complex List (NS-CMIC List)

The growth of China’s defense industry directly contributes to the quality and kind of technology China and Chinese companies can proliferate. The Biden administration’s recent executive action refining the previous administration’s restriction on outbound investment in Chinese military companies is an important step forward. By cutting off investment flows to these companies, the U.S. government will help limit the resources available for their efforts to develop leading edge military and dual-use technology.

In its current version, however, the list does not yet adequately name all companies involved in the Chinese defense industry. Specifically, the list does not include key subsidiaries of major defense SOEs, despite the fact that many of these subsidiaries are independently listed on financial markets. Under the executive order, any entity “owned or controlled by, directly or indirectly,” a company either on the NS-CMIC list or operating in the Chinese defense or surveillance industry can also be listed.[110] Accordingly, the administration should identify additional subsidiaries of NS-CMIC listed companies in order to ensure that these subsidiaries cannot evade U.S. investment restrictions. The Treasury Department should also provide a comprehensive list of additional identifier information, including International Security Identification Numbers (ISIN) and aliases, to better inform investors and improve screening.

Manage the Proliferation Risk Posed by Cooperation with Chinese Universities

Chinese universities contribute to the quality of technology that China and Chinese companies develop and can proliferate abroad. Some of these universities directly contribute to military research projects and in some cases, as described above, engage in economic espionage and export control evasion in the United States. The U.S. government could more actively regulate how U.S. parties interact with some of these universities.

The Commerce Department could list additional Chinese universities connected to the Chinese military on its Entity List and Military End User List, as a means of controlling the flow of U.S. dual-use technology and know-how to these universities. Commerce currently has trade restrictions on the seven major Chinese defense universities (colloquially known as the “Seven Sons of National Defense”) and two other Chinese universities.[111] Based on research from the Australian Strategic Policy Institute and subsequent research conducted by the Wisconsin Project, however, some 50 universities directly affiliated with the Chinese defense industry regulatory agency, the State Administration of Science, Technology, and Industry for National Defense (SASTIND), do not appear on any U.S. government trade control list.[112] These universities receive funding from SASTIND, in collaboration with other ministries, to invest in academic departments and research capabilities related to national defense subjects.

Additional measures to highlight the potential proliferation threat from Chinese universities might include creating a “Chinese military university list” modeled on the Chinese military company list authorized in Section 1260H of the 2021 National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA).[113] The Wisconsin Project has found that if the administration were to apply the 2021 NDAA’s definition of “military-civil fusion contributor” to Chinese universities, at least 61 Chinese universities would fall into this category based on their collaboration with SASTIND or other Chinese military projects.

Publishing such a list, even in the absence of specific regulatory action, could help inform U.S. universities engaging with their Chinese counterparts. While U.S. universities cannot collaborate on dual-use technologies with universities and research institutes that appear on U.S. restricted party lists, they may engage in other forms of collaboration that facilitates the proliferation of U.S. know-how to China. In a 2018 career fair, for instance, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology hosted two universities that are part of the “Seven Sons of National Defense” – Beihang University and Northwestern Polytechnical University – who were seeking to recruit job candidates with advanced degrees.[114]

Support the Development of a CFIUS-like Review Process in Partner Countries

China is expanding its influence in many parts of the world through state policies such as MCF, Made in China 2025, the Strategic Emerging Industries Plan, and the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). Many countries, while welcoming Chinese investment, may not have a process for evaluating the national security risks that it poses. The United States could usefully provide support in this regard, by advocating for and providing technical support on establishing a review process for such investment, modeled on the Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States (CFIUS).

Without such a mechanism for formal review, it may be difficult for U.S. partner countries to evaluate the risk of Chinese investment or acquisitions in strategic sectors. The CFIUS review process may cover a broad range of transactions, which is well adapted to the diversity of risk from Chinese acquisition, from obvious investments in the dual-use or military sectors, to robotics, green energy, medicine and biotechnology, and more. By supporting the creation of such a review process, the United States would create a permanent institutional mechanism within partner countries, which could have a more sustained impact on China’s ability to enter new markets of strategic significance in U.S. partner countries.

Appendix: Chinese SOEs Involved in Proliferation Activities Mentioned in the Prepared Testimony

Aerospace Industry

- Aviation Industry Corporation of China (AVIC)

- Chengdu Aircraft Industry Group (CAIG)

- China National Aero-Technology Import-Export Corporation (CATIC)

- China Aerospace Science and Industry Corporation (CASIC)

- China Space Sanjiang Group Co., Ltd.

- Hubei Sanjiang Space Wanshan Special Vehicle Co., Ltd.

- Wuhan Sanjiang Import and Export Co., Ltd.

- China Aerospace Science and Technology Corporation (CASC)

- China International Trust and Investment Corporation (CITIC)

- China Precision Machinery Import-Export Corporation (CPMIEC)

Nuclear Industry

- China General Nuclear Power Company (CGNPC)

- China National Nuclear Corporation (CNNC)

- Beijing Research Institute of Uranium Geology (BRIUG)

- China Nuclear Engineering and Construction Corporation (CNECC)

- China Nuclear Energy Industry Corporation (CNEIC)

- China Zhongyuan Engineering Corporation (CZEC)

Other

- Beihang University

- China Electronics Technology Group Corporation (CETC)

- China National Heavy Duty Truck Group Co., Ltd. (Sinotruk)

- Nanjing University of Aeronautics and Astronautics

- Northwest Polytechnical University (NWPU)

- Poly Technologies Inc.

Attachment:  Testimony of Valerie Lincy before the U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission’s Hearing on “China’s Nuclear Forces”

Testimony of Valerie Lincy before the U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission’s Hearing on “China’s Nuclear Forces”

Footnotes:

[1] An earlier report by the Wisconsin Project explores this shift. See Matthew Godsey and Valerie Lincy, “Gradual Signs of Change: Proliferation to and from China over Four Decades,” Strategic Trade Review, Volume 5, Issue 8, Winter/Spring 2019, pp. 3-21, available at https://strategictraderesearch.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/Strategic-Trade-Review-WinterSpring-2019.pdf.

[2] “DOE Announces Measures to Prevent China’s Illegal Diversion of U.S. Civil Nuclear Technology for Military or Other Unauthorized Purposes,” Press Release, U.S. Department of Energy, October 11, 2018, available at https://www.energy.gov/articles/doe-announces-measures-prevent-china-s-illegal-diversion-us-civil-nuclear-technology.

[3] For a description of key transfers from China to Pakistan (and other countries) in the 1980s, see: Gary Milhollin and Gerard White, “Bombs from Beijing: A Report on China’s Nuclear and Missile Exports,” Wisconsin Project on Nuclear Arms Control, May 1, 1991, available at https://www.wisconsinproject.org/bombs-from-beijing-a-report-on-chinas-nuclear-and-missile-exports/.

[4] “China and Weapons of Mass Destruction: Implications for the United States,” Conference Report, National Intelligence Council, November 5, 1999, available at https://www.dni.gov/files/documents/China_WMD_2000.pdf.

[5] Evan S. Medeiros and Bates Gill, “Chinese Arms Exports: Policy, Players, and Process,” Strategic Studies Institute, August 2000, pp. 45-47, available at https://press.armywarcollege.edu/monographs/132.

[6] Shirley A. Kan, “China and Proliferation of Weapons of Mass Destruction and Missiles: Policy Issues,” Congressional Research Service, February 26, 2003, available at https://fas.org/asmp/resources/govern/crs-rl31555.pdf; “China and Weapons of Mass Destruction: Implications for the United States,” Conference Report, National Intelligence Council, November 5, 1999, available at https://www.dni.gov/files/documents/China_WMD_2000.pdf..

[7] Pakistan Country Profile (Updated 2020), International Atomic Energy Agency World Wide Web site, available at https://cnpp.iaea.org/countryprofiles/Pakistan/Pakistan.htm.

[8] Guidelines for Nuclear Transfers, Part 1, Nuclear Suppliers Group, October 18, 2019, available at https://www.iaea.org/sites/default/files/publications/documents/infcircs/1978/infcirc254r14p1.pdf. Pakistan has implemented site-specific IAEA safeguard for its civilian nuclear facilities. But it does not allow access to its military nuclear facilities.

[9] “Grid connection for Pakistani Hualong One unit,” Press Release, China National Nuclear Corporation, March 22, 2021, available at https://en.cnnc.com.cn/2021-03/22/c_605154.htm. The first reactor in Kararchi (KANUPP-1), is a PHWR built by Canada that became operational in the 1970s.

[10] “Third HPR1000 unit to build overseas,” Press Release, China National Nuclear Corporation, November 22, 2017, available at https://en.cnnc.com.cn/2017-11/22/c_112681.htm.

[11] “CZEC at a Glance,” China Zhongyuan Engineering Corporation World Wide Web site, available at https://web.archive.org/web/20170122121640/http://www.czec.com.cn/zgzydwgcyxgsywbm/au/caag/index.htm; “Nuclear Power Reactors in the World,” International Atomic Energy Agency, 2012, pp. 29, 71, available at http://www-pub.iaea.org/MTCD/publications/PDF/RDS2-32_web.pdf.

[12] Pakistan Country Profile (Updated 2020), International Atomic Energy Agency World Wide Web site, available at https://cnpp.iaea.org/countryprofiles/Pakistan/Pakistan.htm; “Nuclear Power: A Viable Option For Electricity Generation,” Pakistan Atomic Energy Commission World Wide Web site, available at http://www.paec.gov.pk/NuclearPower/.

[13] “Third HPR1000 unit to build overseas,” Press Release, China National Nuclear Corporation, November 22, 2017, available at https://en.cnnc.com.cn/2017-11/22/c_112681.htm.

[14] “India and Pakistan Sanctions and Other Measures,” U.S. Department of Commerce, Bureau of Export Administration, Federal Register, Vol. 63, No. 223, November 19, 1998, pp. 64322, 64325, 64341, available at https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-1998-11-19/pdf/98-30877.pdf.

[15] Hans M. Kristensen, Robert S. Norris, and Julia Diamond, “Pakistani Nuclear Forces, 2018,” Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, Vol. 74, No. 5, 2018, p. 352, available at https://doi.org/10.1080/00963402.2018.1507796.

[16] Trade data reviewed by the Wisconsin Project; Haris N Khan, “Pakistan’s Nuclear Program: Setting the Record Straight,” Defense Journal, August 2010, p. 36, available via www.scribd.com; Feroz Hassan Khan, Eating Grass: the Making of the Pakistani Bomb, (Stanford: Stanford University Press: 2012), pp. 240, 242.

[17] Wuhan Sanjiang Export and Import Co., Ltd., National Enterprise Credit Information Publicity System, available at http://www.gsxt.gov.cn/; “Brief Introduction of Space Sanjiang,” China Space Sanjiang Group Co., Ltd. World Wide Web site, available at http://www.yzjs.casic.cn/n13740039/n13740062/c13740102/content.html (in Chinese).

[18] Trade data reviewed by the Wisconsin Project; Wu Xuelei, “Development History, Status and Tendency of Foreign Military Truck (Part IV),” June 2001, China Academy of Launch Vehicle Technology World Wide Web site, available at https://web.archive.org/web/20060831204645/http://www.calt.com/information/magazine/200106/016WXL.htm (in Chinese).

[19] Franz-Stefan Gafney, “China, Pakistan to Co-Produce 48 Strike-Capable Wing Loong II Drones,” the Diplomat, October 8, 2018, available at https://thediplomat.com/2018/10/china-pakistan-to-co-produce-48-strike-capable-wing-loong-ii-drones/; Gabriel Dominguez, “Pakistan receives five CH-4 UAVs from China,” Jane’s Defense Weekly, January 27, 2021, available at https://www.janes.com/defence-news/news-detail/pakistan-receives-five-ch-4-uavs-from-china; George Nacouzi et al., “Assessment of the Proliferation of Certain Remotely Piloted Aircraft Systems,” RAND Corporation, 2018, p. 15, available at https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RR2369.html.

[20] Ethan Meick, “China’s Reported Ballistic Missile Sale to Saudi Arabia: Background and Potential Implications,” U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission, June 16, 2014, available at https://www.uscc.gov/sites/default/files/Research/Staff%20Report_China’s%20Reported%20Ballistic%20Missile%20Sale%20to%20Saudi%20Arabia_0.pdf.

[21] Evan S. Medeiros, Reluctant Restraint: The Evolution of China’s Nonproliferation Policies and Practices, 1980-2004 (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2007), pp. 104-108.

[22] Ethan Meick, “China’s Reported Ballistic Missile Sale to Saudi Arabia: Background and Potential Implications,” U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission, June 16, 2014, available at https://www.uscc.gov/sites/default/files/Research/Staff%20Report_China’s%20Reported%20Ballistic%20Missile%20Sale%20to%20Saudi%20Arabia_0.pdf.

[23] Jeff Stein, “The CIA Was Saudi Arabia’s Personal Shopper,” Newsweek, January 29, 2014, available at https://www.newsweek.com/2014/01/31/cia-was-saudi-arabias-personal-shopper-245128.html.

[24] “CASIC DF-21D Unveiled at the Victory Parade,” China Aerospace Science and Industry Corporation World Wide Web site, September 6, 2015, available at http://www.casic.com.cn/n12377419/n12378214/n2354949/n2354967/c2367928/content.html (in Chinese).

[25] Paul Sonne, “Can Saudi Arabia produce ballistic missiles? Satellite imagery raises suspicions,” Washington Post, January 23, 2019, available at https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/national-security/can-saudi-arabia-produce-ballistic-missiles-satellite-imagery-raises-suspicions/2019/01/23/49e46d8c-1852-11e9-a804-c35766b9f234_story.html.

[26] Jamie Withorne, “Saudi Arabia’s Suspect Missile Site and the Saudi Nuclear Program,” James Martin Center for Nonproliferation Studies, Middlebury Institute of International Studies at Monterey, March 26, 2019, available at https://nonproliferation.org/saudi-arabia-briefing-dc/.

[27] Cholpon Orozobekova and Marc Finaud, “Regulating and Limiting the Proliferation of Armed Drones: Norms and Challenges,” Geneva Centre for Security Policy, August 2020, pp. 15-17, available at https://dam.gcsp.ch/files/doc/regulating-and-limiting-the-proliferation-of-armed-drones-norms-and-challenges.

[28] “Updates on Saudi National Atomic Energy Project (SNAEP),” Second Meeting of the Technical Working Group for Small and Medium-sized or Modular Reactor (TWG-SMR), Saudi National Atomic Energy Project, July 2019, p. 15, available at https://nucleus.iaea.org/sites/htgr-kb/twg-smr/Documents/TWG-2_2019/B07_Updates%20on%20Saudi%20National%20Atomic%20Energy%20Project%20(SNAEP)%20for%20IAEA%20SMR-TWG%2020190708.pdf; “China, Saudi Arabia agree to build HTR,” World Nuclear News, January 20, 2016, available at https://www.world-nuclear-news.org/NN-China-Saudi-Arabia-agree-to-build-HTR-2001164.html.

[29] “CNNC and Saudi Arabia Expedite Uranium and Thorium Collaborations,” Press Release, China National Nuclear Corporation, September 01, 2017, available at http://en.cnnc.com.cn/2017-09/01/c_101806.htm.

[30] “Memorandum of Understanding Signed for the Joint Venture Company of the Saudi High Temperature Reactor Desalination Project,” China Nuclear Power Information Network, August 29, 2017, available at http://www.heneng.net.cn/index.php?mod=news&category_id=8?oclnynhfkbtdgmyn&action=show&article_id=46812 (in Chinese).

[31] Emma Graham-Harrison, Stephanie Kirchgaessner, and Julian Borger, “Revealed: Saudi Arabia May Have Enough Uranium Ore to Produce Nuclear Fuel,” the Guardian, September 17, 2020, available at https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/sep/17/revealed-saudi-arabia-may-have-enough-uranium-ore-to-produce-nuclear-fuel.

[32] “President Li Ziying Led a Delegation to Visit Saudi Arabia’s Deputy Minister of Industry and Mining Mudaifei,” Press Release, Beijing Research Institute of Uranium Geology, November 6, 2019, available at http://www.briug.cn/index.php?m=content&c=index&a=show&catid=23&id=1569 (in Chinese).

[33] David Albright, Jacqueline Shire, and Paul Brannan, “Is Iran Running out of Yellowcake?,” Institute for Science and International Security, February 11, 2009, p. 2, available at https://isis-online.org/uploads/isis-reports/documents/Iran_Yellowcake_11Feb2009.pdf.

[34] Prepared Testimony by Gary Milhollin Before the Senate Foreign Relations Committee Hearing: The Arming of Iran, May 6, 1997, available at https://www.iranwatch.org/library/governments/united-states/congress/hearings-prepared-statements/prepared-testimony-gary-milhollin-senate-foreign-relations-committee-hearing-0.

[35] “Implementation of the NPT Safeguard Agreement in the Islamic Republic of Iran,” International Atomic Energy Agency, GOV/2003/75, November 10, 2003, annex 1, p. 1, available at https://www.iaea.org/sites/default/files/gov2003-75.pdf.

[36] For a complete list of Iran’s declared and suspected nuclear sites, see “Table of Iranian Nuclear Sites and Related Facilities,” Iran Watch, updated March 31, 2021, available at https://www.iranwatch.org/our-publications/weapon-program-background-report/table-irans-principal-nuclear-facilities.

[37] “Executive Summary of the Report of the Commission to Assess the Ballistic Missile Threat to the United States,” Commission To Assess the Ballistic Missile Threat to the United States, July 15, 1998, available at https://fas.org/irp/threat/bm-threat.htm.

[38] “Treasury Designates U.S. and Chinese Companies Supporting Iranian Missile Proliferation,” Press Release, U.S. Department of the Treasury, June 13, 2006, available at http://www.treasury.gov/press-center/press-releases/Pages/js4317.aspx.

[39] “Treasury Designates the IRGC under Terrorism Authority and Targets IRGC and Military Supporters under Counter-Proliferation Authority,” Press Release, U.S. Department of the Treasury, October 13, 2017, available at https://www.treasury.gov/press-center/press-releases/Pages/sm0177.aspx.

[40] “New Sanctions under the Iran, North Korea, and Syria Nonproliferation Act (INKSNA),” Press Release, U.S. Department of State, February 25, 2020, available at https://2017-2021.state.gov/new-sanctions-under-the-iran-north-korea-and-syria-nonproliferation-act-inksna/index.html.

[41] “Organization,” China Aerospace Science and Technology Corporation World Wide Web site, available at http://english.spacechina.com/n16421/n17138/n2357690/index.html.

[42] Shirley A. Kan, “China and Proliferation of Weapons of Mass Destruction and Missiles: Policy Issues,” Congressional Research Service, January 5, 2015, pp. 18-19, available at https://fas.org/sgp/crs/nuke/RL31555.pdf.

[43] “Treasury Designates the IRGC under Terrorism Authority and Targets IRGC and Military Supporters under Counter-Proliferation Authority,” Press Release, U.S. Department of the Treasury, October 13, 2017, available at https://www.treasury.gov/press-center/press-releases/Pages/sm0177.aspx; “Report of the Panel of Experts established pursuant to resolution 1874 (2009),” United Nations, S/2013/337, June 11, 2013, pp. 26-28, available at https://undocs.org/S/2013/337; “Brief Introduction of Space Sanjiang,” China Space Sanjiang Group Co., Ltd. World Wide Web site, available at http://www.yzjs.casic.cn/n13740039/n13740062/c13740102/content.html (in Chinese).

[44] “Report of the Panel of Experts established pursuant to resolution 1874 (2009),” United Nations, S/2016/157, February 24, 2016, pp. 39-40, available at https://undocs.org/S/2016/157.

[45] Joost Oliemans and Stijn Mitzer, “N.Korea’s ‘conservative’ display contrasts with past WPK celebrations,” NK News, October 10, 2015, available at https://www.nknews.org/2015/10/analysis-of-new-updated-equipment-in-october-10-parade/; “Group Profile,” China National Heavy Duty Truck Group Co., Ltd. World Wide Web site, available at http://www.cnhtc.com.cn/View/AboutGroup.aspx (in Chinese); China National Heavy Duty Truck Group Co., Ltd., National Enterprise Credit Information Publicity System, available at http://www.gsxt.gov.cn/.

[46] Shirley A. Kan, “China and Proliferation of Weapons of Mass Destruction and Missiles: Policy Issues,” Congressional Research Service, January 5, 2015, pp. 20-21, available at https://fas.org/sgp/crs/nuke/RL31555.pdf; Michael Laufer, “A. Q. Khan Nuclear Chronology,” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, September 7, 2005, available at https://carnegieendowment.org/2005/09/07/a.-q.-khan-nuclear-chronology-pub-17420; S.S. Hecker, R.L. Carlin, and E.A. Serbin, “A technical and political history of North Korea’s nuclear program over the past 26 years,” Center for International Security and Cooperation, Stanford University, May 24, 2018, available at https://fsi-live.s3.us-west-1.amazonaws.com/s3fs-public/narrativescombinedfinv2.pdf.

[47] Cholpon Orozobekova and Marc Finaud, “Regulating and Limiting the Proliferation of Armed Drones: Norms and Challenges,” Geneva Centre for Security Policy, August 2020, pp. 15-17, available at https://dam.gcsp.ch/files/doc/regulating-and-limiting-the-proliferation-of-armed-drones-norms-and-challenges.

[48] U.N. Security Council resolution 2094 (2013), March 7, 2013, p. 3, available at https://www.undocs.org/S/RES/2094(2013); U.N. Security Council resolution 2270 (2016), March 2, 2016, pp. 3-4, available at https://www.undocs.org/S/RES/2270(2016); U.N. Security Council resolution 2321 (2016), November 30, 2016, p. 7, available at https://www.undocs.org/S/RES/2321(2016);

[49] U.N. Security Council resolution 2371 (2017), August 5, 2017, p. 9, available at https://undocs.org/S/RES/2371(2017).

[50] Indictment, United States of America v. Ko Chol Man et al., U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia, Case No. 1:20-cr-32-RC, February 5, 2020, available via PACER.

[51] Verified Complaint for Forfeiture In Rem and Civil Complaint, United States of America v. $4,083,935.00 of Funds Associated with Dandong Chengtai Trading Limited et al., U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia, Case No. 1:17-cv-01706, August 22, 2017, pp. 2-3, 15-16, 19-20, available at https://www.justice.gov/usao-dc/press-release/file/992451/download; “Treasury Targets Chinese and Russian Entities and Individuals Supporting the North Korean Regime,” Press Release, U.S. Department of the Treasury, August 22, 2017, available at https://www.treasury.gov/press-center/press-releases/Pages/sm0148.aspx.

[52] “Report of the Panel of Experts established pursuant to resolution 1874 (2009),” United Nations, S/2020/840, August 28, 2020, pp. 43-44, available at https://undocs.org/S/2020/840; “Report of the Panel of Experts established pursuant to resolution 1874 (2009),” United Nations, S/2021/211, March 4, 2021, p. 56, available at https://undocs.org/S/2021/211; “Two Chinese Nationals Charged with Laundering Over $100 Million in Cryptocurrency From Exchange Hack,” Press Release, U.S. Department of Justice, March 2, 2020, available at https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/two-chinese-nationals-charged-laundering-over-100-million-cryptocurrency-exchange-hack.

[53] U.N. Security Council resolution 2397 (2017), December 22, 2017, p. 4, available at https://undocs.org/S/RES/2397(2017).

[54] “Report of the Panel of Experts established pursuant to resolution 1874 (2009),” United Nations, S/2020/840, August 28, 2020, pp. 33-34, available at https://undocs.org/S/2020/840.

[55] “Report of the Panel of Experts established pursuant to resolution 1874 (2009),” United Nations, S/2021/211, March 4, 2021, p. 48, available at https://undocs.org/S/2021/211.

[56] “Treasury Sanctions North Korean Overseas Representatives, Shipping Companies, and Chinese Entities Supporting the Kim Regime,” Press Release, U.S. Department of the Treasury, January 24, 2018, available at https://home.treasury.gov/news/press-releases/sm0257; “Report of the Panel of Experts established pursuant to resolution 1874 (2009),” United Nations, S/2019/171, March 5, 2019, p. 32, available at https://undocs.org/S/2019/171.

[57] Since 2018, the United Nations has restricted the sale of refined petroleum products to North Korea, with the first 500,000 barrels exempted each year. See U.N. Security Council resolution 2397 (2017), December 22, 2017, pp. 2-3, available at https://undocs.org/S/RES/2397(2017).

[58] “Report of the Panel of Experts established pursuant to resolution 1874 (2009),” United Nations, S/2019/171, March 5, 2019, p. 7, available at https://undocs.org/S/2019/171; “Report of the Panel of Experts established pursuant to resolution 1874 (2009),” United Nations, S/2020/151, March 2, 2020, pp. 7-8, available at https://undocs.org/S/2020/151; “Report of the Panel of Experts established pursuant to resolution 1874 (2009),” United Nations, S/2021/211, March 4, 2021, pp. 14-15, available at https://undocs.org/S/2021/211.

[59] “Supply, sale or transfer of all refined petroleum products to the DPRK,” 1718 Sanctions Committee (DPRK), United Nations, available at https://www.un.org/securitycouncil/sanctions/1718/supply-sale-or-transfer-of-all-refined-petroleum; “Report of the Panel of Experts established pursuant to resolution 1874 (2009),” United Nations, S/2019/171, March 5, 2019, pp. 7-8, 81, available at https://undocs.org/S/2019/171; “Report of the Panel of Experts established pursuant to resolution 1874 (2009),” United Nations, S/2020/151, March 2, 2020, pp. 7-8, available at https://undocs.org/S/2020/151.

[60] “Report of the Panel of Experts established pursuant to resolution 1874 (2009),” United Nations, S/2020/151, March 2, 2020, pp. 16-19, available at https://undocs.org/S/2020/151.

[61] Christoph Koettl, “How Illicit Oil Is Smuggled Into North Korea With China’s Help,” New York Times, March 24, 2021, available at https://www.nytimes.com/2021/03/24/world/asia/tankers-north-korea-china.html; “Report of the Panel of Experts established pursuant to resolution 1874 (2009),” United Nations, S/2020/151, March 2, 2020, pp. 106-108, available at https://undocs.org/S/2020/151.

[62] “Report of the Panel of Experts established pursuant to resolution 1874 (2009),” United Nations, S/2021/211, March 4, 2021, pp. 28-32, 218-224, available at https://undocs.org/S/2021/211.

[63] “Report of the Panel of Experts established pursuant to resolution 1874 (2009),” United Nations, S/2019/171, March 5, 2019, p. 32, available at https://undocs.org/S/2019/171.

[64] “Company Profile,” Shanghai Zhen Tai Instrument Co., Ltd. World Wide Web site, available at http://en.shzhentai.com/intro/1.html.

[65] “Report of the Panel of Experts established pursuant to resolution 1874 (2009),” United Nations, S/2017/150, February 27, 2017, p. 27, available at https://undocs.org/S/2017/150.

[66] “Report of the Panel of Experts established pursuant to resolution 1874 (2009),” United Nations, S/2017/150, February 27, 2017, p. 28, available at https://undocs.org/S/2017/150; “North Korea Ballistic Missile Procurement Advisory,” U.S. Departments of Commerce, State, and the Treasury, September 1, 2020, available at https://home.treasury.gov/system/files/126/20200901_nk_ballistic_missile_advisory.pdf.

[67] List of Sanctioned Entities, U.S. Department of State, available at https://www.state.gov/key-topics-bureau-of-international-security-and-nonproliferation/nonproliferation-sanctions/.

[68] “Karl Lee Charged in Manhattan Federal Court with Using a Web of Front Companies to Evade U.S. Sanctions,” Press Release, Federal Bureau of Investigation, New York Field Office,, April 29, 2014, available at https://www.fbi.gov/contact-us/field-offices/newyork/news/press-releases/karl-lee-charged-in-manhattan-federal-court-with-using-a-web-of-front-companies-to-evade-u.s.-sanctions.